All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

King David, Introduction

I remember life before this, before the Blackdown. That’s what we all called it anyway. I remember the Old-Thinkers (who weren’t called Old-Thinkers at the time) talking about it during their lectures. The Solar Maximum they called it. They warned us, and we didn’t listen to them. No one expected what would happen.

How mystified I was at first. It was nighttime, and I was with her. It was dark, the only illumination coming from the warm, but lifeless lighting of the street lamps, and the dim twinkling of the stars. Suddenly, though, we were basked in an almost unworldly blue-green light. We looked up, not saying a word to each other, as everyone else around us did as well. Never before in history had it been recorded this far from the Arctic Circle. Its colors danced before our eyes in the night sky, from an aqua blue to a light green to reds, to pinks, and back again. Never before had I seen so many colors in nature all blending together and dancing right in front of us, like mystical beings locked in a perpetual and giddy dance of color in the night sky. Both our breaths were taken away. We didn’t realize the terror that this epitome of benevolence heralded though.

I’m no Old-Thinker, I don’t claim to be, but I don’t need to be to know that somehow that amazing spectacle of lights caused, if indirectly, the Blackdown. Within moments of its departure, which was as sudden and silent as its arrival, we noticed that we were no longer standing in that warm and lifeless light. The street lamps had dimmed. All of them had. With only the moon to guide us we fumbled our way back to our car and, with curiosity on our minds drove back to the apartment. Nothing worked. The light switch would not heed our orders; the television would not spring to life to show us how the exact same thing had happened to every home, every apartment block, every county, in not just our country, but in the entire hemisphere.

I took out my phone to call the power company. No service. I stepped out onto our balcony to test there. No service. I stepped outside to the dark and cold sidewalk. No service. I tried her phone instead. No service. Where ever I went, there was no service. That morning the streets buzzed and hummed with the slightly panicked chatter of our town’s inhabitants. Very quickly two things were realized. Everyone had no power; no cell phone service, no television, no radio, no contact with the world. The second thing we all realized was that no one was coming to get us. People were organizing into convoys to travel over the great hill that cut us off from the metropolis on the other side. I call it “the metropolis” because it’s been so long since I’ve heard its actual name spoken. I remember nothing about it, only that all of my family is still there. I left the metropolis to be taught by the Old-Thinkers (who, again, were not called Old-Thinkers during the time which I left). That was my ultimate objective: get to the metropolis and survive as a family. Everyone assumed that since it was such a large city, they would find help there, since help was clearly not coming to them. We stayed though, her and me. We kept hope while the world around us seemed so quick to forgo it.

For a few days this hum and buzz rung out through the streets, but it soon yielded to the sound of car engines as caravan after caravan made the journey out of the town and over the hill, where they hoped to find aid. After a few days, with no electricity to maintain them, the water pumps broke down, and all running water stopped. I thank God that I foresaw this and we were able to bottle enough water to last us for some time. For at least two months after the Blackdown we lived in our apartment. We desperately tried to continue as normal of a life as we could. I would go down to the grocery store and attempt to buy food. But soon, as I discovered, people ran out of cash, and with no ATMs to hand out cash, the banks were run dry. Occasionally we’d see a bank’s armored van heading towards the direction of the hill, as if to return with a resupply of currency, but they never returned.

After all the caravans had left, there was silence. An eerie silence that was only broken by the sound of shattering glass and blaring car alarms as those who had been left behind broke into abandoned cars and stole them out of desperation. They left in a hurry, not even strapping on their little possessions to the top of the vehicle. They were all too eager to escape what they thought was the jaws of some hungry, ferocious beast. Little did I know it, but we would soon meet these jaws.

Now I may not have known it at the time, but I know now that survival experts say that there are five main and key points to survival: Water, Food, Shelter, Fire, and Security. In my naivety I had completely overlooked the final point, that all important fifth point of survival. My mistake would quickly be realized to me.

We call them Food-Drifters. Mainly, from what we understand, at the time just before the Blackdown they were penniless, homeless, without family or possessions. They were the men and women who didn’t know how to hotwire cars, or live peacefully in a society suddenly turned lawless, and thus were left behind during the Great Caravan Immigrations. They lived together, in an almost commune society, though they had no permanent home, nor did they make any food for themselves. They rely on numbers, sheer manpower. They came so suddenly I didn’t have much of a chance to react. We were both without weapons and so we fought them with our hands and fists as they swarmed through our broken doorway in seemingly endless waves. I remember standing next to her in front of the master bedroom, and fighting uselessly against them. They are piranhas. They descend in numbers so numerous they can’t be counted as they frenzy on a ripe and juicy steak, then leave in such a hurry they seem to vanish, leaving little left for the poor souls they took it from. Nearly everything was stripped down to the walls. They took everything, even the refrigerator, the sinks, the counter-tops, everything.

The only room that was untouched was our master bedroom, where we kept some spare food and water, but nearly enough to sustain us there. So with heavy hearts we decided to leave our beloved home. We broke the spindles of the bed and sharpened the splintered end to fashion a primitive weapon. On the other end we tied together pieces of the broken footboard to form a blunter, less lethal end to the weapon. We gathered everything we could carry, however trivial it may have been. And after about four months after the Blackdown, we finally abandoned the shelter we once called home.

There is a river that runs near the outskirts of the town. Though there are few, if any fish, to be caught in its waters the soil around it is rich with nutrients, and therefore teeming with fruits and berries ripe for the picking. I knew by looking at our supplies that we didn’t have enough food or water to last the five day hike to and up the hill, let alone the trek down the farther side. So, despite every fiber in my body urging me to do otherwise, I led us in the opposite direction. We headed away from the hill, from family, and towards the river, towards survival.

After about three days hike we ended up at the riverbank. We chose to set up a very primitive camp along the banks. We were masked from unwanted visitors by the thick undergrowth. We pitched a tent using the sheets from our bed. Every morning we would wake up and one of us would take about ten paces and collect the day’s water from the river, while the other would start a small fire so as to boil the water. We lived almost entirely on fruits, roots, and herbs. Occasionally we would find a wild duck along the riverbed that, despite both of our reservations, we would butcher and have well desired meat that night for supper.

Almost four months more we lived this way, though the days at some points bled together. We began to tell ourselves that the worse was over. We would camp out here at our riverbank until a search party finally found us, though neither of us dared suggest when exactly that would be. We were regrettably evicted from our second hovel not by man, but by Mother Nature. As fall began to turn to winter, the river bank began to swell. What once took ten paces to get to the bank’s edge soon became eight paces, then five, then three. As the riverbank approached, we began to notice a disturbing inconvenience. As the ground became saturated with water, our feet sank inches into the ground with every step. The large stick to which we secured the center of our tent to the ground with soon began to sink in the mud. It was during the worst rainstorm since the Blackdown that she and I wordlessly decided that living here was impossible. So with a heart almost as heavy as our sopping wet clothes and supplies, we gathered what we could and left again.

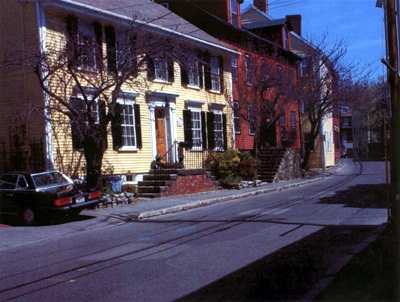

We were fortunate in that only a fifteen minute walk from the river bank laid a nice and quaint suburb. All of the houses were cold and long abandoned, the driveways were empty, the lawns flooded and swampy from the intense rainfall. I quickly decided that in order to gain adequate shelter, we would have to become squatters, something both of us would have greatly frowned upon prior to the Blackdown, but our situations have all changed since then, and we knew that this land was now lawless.

I searched for a house large enough to hide in if we had to, but small enough to not be ostentatious. That essential fifth point of survival, which I had completely neglected before, now proved to be the determining factor in our poor and penniless house hunting. Finally, we both settled upon a house, which to our great joy we found had been raided by the Food-Drifters before our arrival. We hoped that this meant that if we remained subtle enough in our living here, Food-Drifters would never think to research the house, our house.

We entered through an already broken window, and were meticulous in making sure we placed no items in any range of view from the window, the window that, in our opinion, was the viewing glass of the outside world into our home. Home, how the definition has changed so quickly. For me, home used to be the place where you could return from a long day and relax in front of a warm fire, watch television, surrounded by loving family and friends, no care at all for the outside world. Perfect comfort, that’s what home meant to me. And indeed it was this home that occupied my dreams every night before I awoke and was forced to live the pitiful, impoverished, and miserable existence of our lives.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.