All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

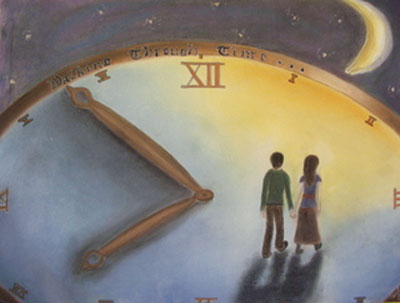

The Dream Years

There are faces gathered around me. There is warmth. Hands are reaching out. I close my eyes.

My mother holds my shoulders, running behind me, pushing me as I pedal the tiny circles that are combating the force of gravity on my little body. I speed down the block, yelling and smiling as she stops in the middle of the street and cheers.

“Go Avery! You’re doing it!”

Eventually I move out of her sight, and she becomes a small waving dot on the horizon. Now I slow my frantic legs, cruising on an absolutely silent street past houses pink, white, yellow, blue, pink, white, yellow, blue going on forever, separated by emerald lawns and shimmering asphalt, all clean lines, all empty. I stop and go into a house, a light blue one. The TV blares the theme music from The Andy Griffith Show. The house is clean and empty, just like the rest of the world.

I drift into the living room and sit on the couch next to Nelson Mandela. On the screen Andy Griffith is telling Don Knotts about being a good sheriff.

“You gotta be truthful to be a good sheriff! How can you expect people to trust you when you’re lying all the time about your coke problem? Dr. Drew thinks you can recover, but we can’t do it without your help. Have you thought about moving into the house? The first step is admitting that you have a problem.”

I turn to face Nelson. “I’m dreaming right?”

He turns away from the TV and gives me a long look.

“Not exactly,” he says. “You’re living again. You’re starting fresh. Dreaming is the shortest distance between two points. You closed your eyes back there but you were fully aware that you’d never open them again. So think of this as your life.”

I shake my head, confused. Someone is knocking softly on the front door; I get up to answer it. The screen is closed, but the door is open and I can see the silhouette of a girl. It’s a girl I know. I open the screen and she smiles; the dimples under her eyes crinkle up.

“Our house never looked like this, Avery. You don’t even like light blue.”

Then she leans through the doorframe and kisses me, being familiar and sweet. There is nothing outside the kiss when I close my eyes. I can’t imagine any other world, house, room. There is only the feeling. I open my eyes.

We’re swimming in the ocean, spitting from all the salt and drying out from the relentless sun. She smiles at me, her eyes red from the water. Her skin is so smooth and even; I long to touch it, but something is happening to me. My hand is moving across the space between us at a snail’s pace, slower, I can’t put my hand down now because it would seem so weird, but why is it moving so slowly?

“I’m dreaming right?” I ask her. She shakes her head sadly, looking down. “What else could this be? It’s just like a dream, like I’m living in my head.”

“That’s exactly right, Avery. You’re living in your head.”

How long has it been since we were in the house? Since I was riding my bike? Since I saw my mom? Years, it feels like. Or maybe seconds.

We swim back to the beach and lay naked in the sand, letting the heat completely overtake us. It is only when we realize that the sun has set and that our clothes are covered in butterflies that we get dressed. Later, as we are walking back to the city she turns to me and says,

“Do you know where we are?”

“Yes” I answer, fully confident that we are wherever I say we are: I have started to figure out the rules. The beach and boardwalk disappear as I remember the little house on Pearl Street.

It’s yellow, with white trim. (She was right of course, I always hated light blue). There are a lot of people in the house, a party. She wanders into the kitchen, while I start chatting with an old work acquaintance, Bob Mapplethorpe.

“Bob, I’m pretty sure I’m dreaming. Isn’t there a test or something I can try?” Bob shakes his head morosely and looks back into his drink. I wonder if he can hear me.

I yell “Bob! How can I tell if this is a dream or not?!” but he doesn’t respond.

I’m about to walk away when he whispers, “You know you’re dead right?” His words ring loudly above the chatter of the party. Suddenly we are alone, Bob and I. Bob begins explaining in earnest.

“You can always tell when the girl is in the dream. You know how in most dreams you’re the main character and everyone else drifts in and out? It’s not your run-of-the-mill REM cycle when the girl of your dreams is reenacting your life with you. This is urgent. How long has it been since you’ve seen her?”

“Seven years.”

“How can you be sure you’ll ever see her again? You have to do it right this time, because there’s really no turning back, for either of you. She can’t tell you anything, of course, because we’re all in your head. Everything you’re hearing you already knew. But enjoy the dream years, make them last. This is your only chance.”

After Bob finishes speaking I sit down quietly on the floor and let my thoughts wander. Bob plops down, Indian-style, next to me. Accordion music is being played softly in the kitchen, and we listen for the snatches of melody that aren’t absorbed by the sturdy scarlet walls. I study Bob, who has set down his drink and is gazing blankly into space. He’s wearing his work clothes, a plain blue single-breasted suit with a green tie. I suddenly realize that I’m wearing my work clothes too, a very similar combination. I’m also wearing glasses that I don’t remember needing before. Bifocals. I close my eyes.

Sunlight surges in bold, happy streaks through the French doors in the bedroom. I rub my eyes a little and lazily stretch my arms to touch both sides of the empty bed. After a little more stretching and yawning I am up and at ‘em, following the scent of coffee into the kitchen. As I pour myself a cup, I survey the beautiful view of the garden from the window above the sink. I spot her almost immediately. She’s outside in the golden sun, tending to the Tulips and Marigolds, watering the Rosemary and Thyme. I watch silently, breathing deeply and filling myself with the awareness that this is the last time I will ever remember this moment.

“I could stop it here,” I think. “I could just hit pause and stay here forever, in limbo, watching my wife weed the garden on an April morning.” But then she turns and smiles and I know I could never be satisfied with the memory. I’m suddenly glad that I have the chance to see her right now, again. My beautiful wife, weeding the garden on an April morning. I sit down at the kitchen table and begin reading the paper. The sky darkens significantly, and the door bursts open as she clatters in, visibly perturbed.

“Hon, I know the service starts at three today, but don’t you think we ought to get there a little earlier?” The service? What service? I play along and say,

“Sure, let’s just go now.”

I’m sitting in the first pew of a small Presbyterian chapel in Arizona. My father’s body is in the coffin in front of the pulpit. My wife is sitting next to me, holding my hand. I am weeping. Mrs. Mellon, my first grade teacher, is the priest doing the ceremony. She’s reading the most beautiful eulogy I have ever heard.

“When I find myself in times of trouble Mother Mary comes to me speaking words of wisdom, let it be. And in my hour of darkness she is standing right in front of me speaking words of wisdom, let it be.”

I close my eyes and put Mrs. Mellon’s words in my heart. My wife, my beautiful, amazing, incredible wife squeezes my hand. This means it’s time to go. We walk out of the empty chapel and right into the suburbs of my childhood. Each street laid at precise right angles, each house painted according to the pattern: pink, white, yellow, blue, pink, white, yellow, blue. The sun is setting over the empty neighborhood.

I whisper, “How can I leave you now? You were gone for seven years. Seven years. How can I go?” She touches my wrinkled cheek and says,

“Let it be.”

Then she lets go of my hand and I float into the rapidly darkening sky, turning and waving goodbye. I am soaring over streets and parks, schools and buildings. The wind blows a cool, even stream against my face, drying my tears. I let my arms rest by my sides as I ascend gently above the world. I close my eyes.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.