All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Silence of Marbles

She found the first marble when she was on a walk with her mother. It was a bright, sunny day, and it twinkled enchantingly from where it lay among blown-away newspapers and other such street detritus. She stopped, as if to tie her shoe, and scooped it up in one quick movement. Putting it in her pocket, she didn't look at it again until she got home and was safely in her room.

Taking it out, she brushed off the dust, and held it up to the light. It was a blue marble, as deeply blue as the clear, calm ocean. Turning it this way and that, she admired her find, noting that she could even see her warped reflection in it. After washing it with soap and water, she placed it reverently on her shelf, among numerous other knick-knacks, and went down for dinner.

The next time she found a marble, she wasn't quite so lucky. It was a ways off from the path they always took, not so far that she couldn't spot it, but too far. Slipping her hand out of her mother's, she ducked under a hanging tree branch and grabbed it, but of course her mother saw. “Oh, Annie, what have you picked up this time off the street? How many times do I have to tell you? You don't know where it's been!” Seeing how Annie tried to conceal it, sheepishly, behind her back, she added, “You know I saw you; now show me.”

With a defeated sigh, Annie proffered the glass sphere. This one was one of the clear ones that has flares of opaque pastel colors whorled and frozen in the middle; it seemed to her like a little winter day, with the watery sun and sky in the middle of cold and snow. It reminded her of a certain water, a certain sky, but she chose not to consider that. Her mother shook her head. “Put it down!” Annie hesitated; her lip trembled ever-so-slightly. “I know it's very pretty, but put it down!” Dejected, she started to toss it aside; her high, pale cheekbones flushed. Her mother relented. “Oh, all right. If that thing is so important to you, keep it. But you had better wash your hands well when we get home.”

Annie brightened, and they went on with their walk.

It was dinnertime again. There were none of her mother's friends over, for the first time in a while, and the expansive mahogany table looked emptier than usual, with just the two of them. The grandfather clock on one side of the room monotonously, heavily, marked the seconds. When it gonged out seven o'clock, Annie jumped. So did her mother, who then laughed, nervously, and continued to eat the mashed potatoes. Annie kept her head down, chewing her food at a furious rate, and then got up once the plate was clear.

Her mother looked very small in that large, dark room.

Annie sat back down.

Finally, they had both finished, and her mother got up, brushing the crumbs off of her somber, dark clothes. She hadn't worn any of her usual, brightly patterned and cheerful dresses since back then. Annie missed them.

Standing uncertainly, as if she'd forgotten what she was going to do, her mother hesitated before picking up the plates. Then she paused again, sat back down, and buried her face in her hands.

Uncomfortable now, Annie started to leave again, but thought better of it and pulled up a chair next to her. Her mother looked up, and her eyes were now filmy and red-rimmed; she hugged her daughter tightly, and, with a barely-contained tremble in her voice, pleaded, “Oh, Annie, Annie, won't you say something, dear? Just one word? Just – just...”

Hot tears rushed to Annie's eyes, and she extracted herself from her mother's clinging grasp and shut herself in her room. She stayed there all evening, lying on her bed and staring at the white-washed ceiling, and cried herself to sleep again.

After the second marble, she began to find them with increasing regularity. Stuck between a sewer grate, trapped in a sidewalk crack, lying among a tangle of fallen leaves, catching her eye here and there and wherever she went. Her mother ceased protesting after the first few. Annie also began to carry around a few at a time in her pocket; they almost become amulets to her, tokens of protection. She often took one out to stare at, polishing carefully with the edge of her shirt until she could see her reflection. Her mother seemed to not be able to decide whether she should worry about this new preoccupation or whether she should let it be.

One evening, when they were walking again like they always did, they passed a playground full of children about Annie's age. Shouting, laughing, running about in the fading light within which the summer day still trembled. A marble rolled down the grassy, sloped hill towards them, and out of habit, she snatched up the marble. Of course, as Annie belatedly realized, there was a girl running after it. Her mother glanced at the girl, glanced at Annie, and stepped aside to let them sort it out.

The girl was a dark-haired brunette, with a simple, white smile that softened her features. When Annie reached out, apologetically, with the marble, the girl shook her head. “It's all right, you can keep it. I seen you collecting them.”

When Annie pocketed the marble, she turned away, back towards her mother, but the girl remained there and so she felt required to stay. Awkwardly, she slid her hands into her pockets. “You don't talk much, do you? That's all right. Do you want to come play with us? If your mom says it's okay...”

With a gentle shove from her mother, she followed the girl, who continued her incessant chatter, as if to make up for her companion's silence. “My name's Sarry. What's yours? Actually, it's fine, you don't have to tell me. You really don't like talking, huh? We're going to play tag. Or we can play marbles, but we just played that, and I lost all my best ones, so I don't wanna play again. But we can do whatever you want. You can come over to my house sometime. There's a doggie, Maybug, and I have a little brother but he's all dirty all the time and no fun to play with, we just moved here by the way...”

After that one evening, they were fast friends. Sarry didn't mind that Annie never said a word, and that was already enough for the both of them, for none of the other children could tolerate either Sarry's constant interruptions nor Annie's strange muteness (they had heard though what happened to her, they knew, but still her refusal to speak was a barrier). As a pair, however, they were easily compatible. This made both Annie's and Sarry's mothers quite happy, for the time being.

Annie knew that her mother's pillow was still damp at night and that, when she kissed her cheeks, they were still salty like the sea, but she found it easier to draw away and hide her guilt now that she had Sarry. She began to attend school again; the teachers treated her kindly and very, very gently as though they were afraid she would shatter, at first. At first they made her come to a stuffy, grey-walled room, where she had to draw pictures for a petite and pouty-lipped woman and then resist the woman's subtle attempts to get her to talk; however, her mother called the school one day after noticing how Annie returned in tears with the crumpled and smeared drawings from these sessions in hand, and she didn't see the woman again. After that, the teachers began to mostly ignore her, for Sarry easily masked her presence, and she could quietly work on crossword puzzles about caterpillars and bugs without being called out to answer questions about the aforementioned creatures.

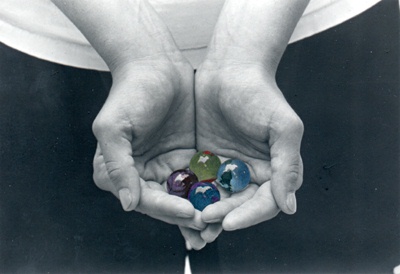

Whenever she had a free moment, she would pull out a marble and roll it back and forth on the table, or between her palms, the smooth, cool touch of glass calming and reassuring her. Her whole shelf was now covered in them, all of them blue, white, or clear, shimmering like the pebbly scales of some strange beast. Only her mother and Sarry had seen her collection; her mother fretted, but allowed it to stay, and Sarry was simply amazed by the variety and sheer quantity of them. In the early morning, a sunbeam would always creep close and then gently touch them, causing bright streaks of light to color the otherwise plain walls and ceiling. Annie loved waking up early to see the spectacle, and was always a little bit sad when it slowly faded away as the sun rose higher.

She could live with this, Annie decided. As long as she had her marbles and Sarry, she could never ever say a word again, because she shouldn't be allowed to speak after what happened. She'd made up her mind on that a long time ago now. And, having made up her mind, nothing in the world could change it, not even her poor dear mother's entreaties.

A few years later, nothing had changed; all was still mostly right with her world, except that they had both grown taller and her mother's hair had grown paler every time that day in the year came around again. She was coming home from school, Sarry in tow. “We're coming to your house today, right? Yeah! I like it at your house, I've told you before, it's so pretty with all the things... your mom is still sad about your father, though... but that's okay, I think she's getting better. I mean, you must have noticed, she only wears black on a few days of the week now. Your room is really nice, you know, it's not as big as mine but I think it's much much nicer, with all the marbles... I've told you all this before, haven't I? Ha! Anyway...”

Her mother opened the door, and Annie paused for a moment upon seeing her. There was a strange, set expression on her mother's face, worn and tired and pallid though it was. She kissed the top of Annie's head, and told Sarry, “Come on in, your mother already called to tell me you're coming over.” After giving her mother a quick hello-hug, Annie ran down the dim corridor with Sarry panting along behind her. She flung open the creaky door that never shut properly, and started towards her desk, where she and Sarry usually did their homework together.

Annie stopped short; Sarry almost ran into her.

The marbles were gone.

“Did you move them?” Sarry asked, noticing their absence as well. Annie shook her head in reply, a panicky feeling rising up in her throat, and her hand went to the marble in her pocket that day, the very first one she'd found. She realized her mother was standing in the doorway. “Annie...” she started gently.

Being a smart girl, Annie quickly put two and two together. She shoved past her mother, and ran out the door. “Annie! I – Annie!”

But she was already out the door, out the door and running again with Sarry behind her. In the distance, she heard her mother faintly crying, “Annie! Come back!”

She was racing down the street, simply trying to get away, away. Her marbles, her precious jewels, were gone, and it was her mother's fault. Gone, gone, gone, the wind whistling in her ears screamed, gone and it's your fault...

Faster and faster she ran, past the point where the sidewalk gave way to grass and the beginnings of a wood, through the trees, leaping over fallen logs and branches and not noticing when her feet began to sink into a mixture of sand and dirt, continuing to run long after the hardly begun trees turned to dunes and the ocean was in view. She only stopped when she hit the water, and a salt spray engulfed her.

Someone yanked on her arm. It was Sarry, flushed and chest heaving. “Annie!” she whispered. “Annie, Annie, don't go in, don't.”

Sarry wasn't sure for a moment that Annie wasn't going to run into the surf, for she turned to her with strangely gleaming eyes and looking like a hunted, wounded animal. But Annie acquiesced, slowly backing away from the waves until she was standing on dry, solid ground, and then collapsed. Her shoulders shook with great, heaving sobs that trembled through her whole body. Sarry sat down next to her, and held her friend. For once, not knowing herself exactly why, she did not utter a word.

Eventually the tears that soaked the whole front of her shirt began to ebb, and Annie lifted her head, face red and stricken.

“It was my fault,” she said softly.

For a moment, mute amazement showed on Sarry's face, but that moment quickly passed. She hugged her friend tighter, trying to comfort her, and listened to her confession without comment nor judgment. “It happened sort of a long time ago now -” her voice, dry and unused for years, cracked. She kept going. “A long time ago, before I met you. A few weeks before I met you. My dad and I, we were at the beach, in the winter – it was cold, really cold, but I'd wanted to see the water. All of a sudden, he – I – I was playing with this kite, my favorite kite, you know, and it seems -” she stopped again, and her chest started to heave once more, but she controlled herself. “I... can't say it, it's just so – so – stupid and childish and...” She looked at Sarry beseechingly, and Sarry gently urged her, with a cautious and worried look, to keep going. “You see, the wind was blowing hard, and the kite slipped and blew out over the water. It was floating, only a few feet away from shore, and I was crying and sobbing and having a tantrum because he'd given that kite to me only a few days ago and I'd loved it from first sight. And so my dad...”

Tears started slipping from her eyes again, and she wiped her face hurriedly. “It looked so close to shore that my dad... he went in to try and grab it, and – the waves, and he was struggling, so quietly, and the fabric got tangled around him -”

He'd looked so very peaceful when they had finally pulled him out, the cheerful and vivid colors of the fabric a sort of cloak or shawl around him that looked almost silly.

“He went down, and I just stood there, all I did was stand there. I couldn't shout, all I did was watch, I didn't even try to go in and help. Can't you see?!” She stood up again, fretfully, faced Sarry. “Can't you see?! It was all my fault because I didn't say anything! All my fault!” Annie made another sort of movement towards the ocean, but Sarry grabbed her arm again. She sagged and seemed to give up something, then started to speak again, with difficulty. “I know what you're going to say. You - you're going to say that it wasn't really my fault, that I was too young to realize. You're gonna say that staying silent won't fix anything, that I shouldn't.... not talk. But – I can't help it, I couldn't help it...” They stood for a while, watching the waves and the wind, and a sort of calmness came onto Annie's face. “You know, the marbles helped, they really did. I don't know why, but having one in my pocket was like – like having a little charm.”

Annie pulled out that first one, and held it, and gazed at the blue light within that seemed to match the water. Sarry closed her hand over it, and simply told Annie, “It will be okay.”

Taking it from her friend's hand, she threw it as far out as she could. They watched the splash, and it was gone. “Marbles aren't a replacement for speaking, even if that's how I met you,” Sarry said. Annie replied, “I know.”

She took her friend by the hand, and they turned away from the waves and memory. They began to make their way between the dunes, back the way that they came, towards Annie's house and mother.

“I'll manage without the marbles,” Annie said when her mother's astonished face greeted them, and tears of joy now sprang from both their eyes.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.